Who invented the piano? This monumental feat is credited almost entirely to one person: Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1751). A native of Padua, Italy, Cristofori is responsible for the innovations that define what makes a piano, a piano today. Later, further innovations by Sébastien Érard, Johann Andreas Stein, Americus Backers, and John Broadwood would create the piano features many of us take for granted today.

Let’s trace the history of the piano through these innovators.

Table of Contents:

Subscribe to The Note for exclusive interviews, fascinating articles, and inspiring lessons delivered straight to your inbox. Unsubscribe at any time.

To fully appreciate the inventor who invented the piano, it helps to know a bit about the instruments that came before.

The hammered dulcimer is an early ancestor of the piano. It uses a very simple version of the piano’s mechanism: hammers that hit strings to create sound. The difference is that the dulcimer requires the player to hold the hammers, whereas later keyboard instruments have a controller (keyboard) to make this more efficient. Hammered dulcimers are common across cultures, from Europe to Asia to the United States.

The clavichord was played in the Middle Ages all the way to the Baroque and Classical eras. This is a small, boxy instrument whose strings are struck by a brass tangent. Clavichords are pretty quiet, so they were used more for personal home enjoyment than performance. In some fretted clavichords, multiple notes share the same string, so playing those notes together is not possible.

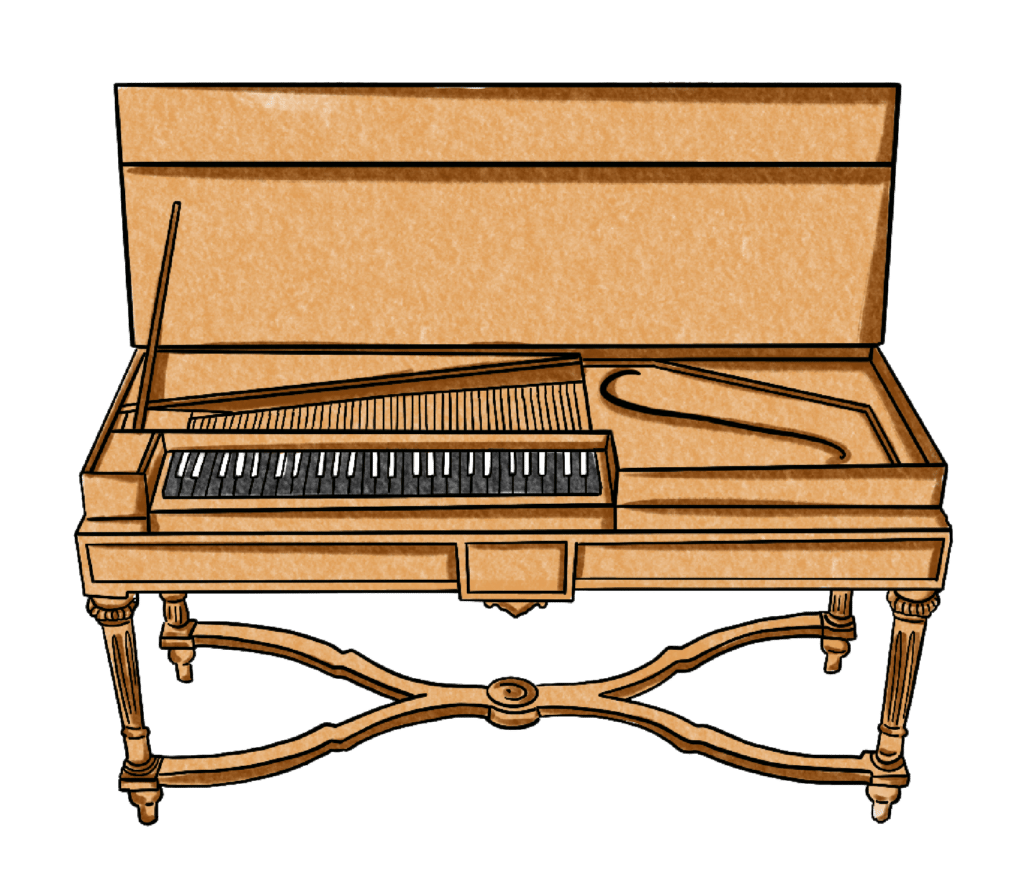

The harpsichord is still sometimes used today. Its strings are plucked, not hammered, and many harpsichords have two keyboards, one on top of the other. Harpsichords have a bright sound and were used to play continuo (a type of accompaniment) in Baroque music—something you can hear in Vivaldi and Bach compositions. Harpsichords remained popular even when pianofortes arrived.

Bartolomeo Cristofori was born in 1655 in Padua, Italy. In 1688, he began working in the court of Grand Prince Ferdinando I de’ Medici, who was a well-known patron of the arts. In those days, earning a living in the arts meant working for a wealthy noble such as a prince or king. This may be why Cristofori is not a mainstream name: not much is known about him because he was seen as an employee of a noble’s court.

While it may seem unfair that Cristofori never got the fame he deserved, he may never have had the time, money, and resources to create the piano as we know it without the patronage of the prince. Ferdinando I was an instrument enthusiast who granted Cristofori a workshop and apprentices to pursue his life’s work.

We can presume 1700 as the birth year of the pianoforte thanks to a few historical records. An inventory of all of the Grand Prince’s instruments lists an “arpicimbalo” that was “newly invented by Bartolomeo Cristofori.” In a 1711 description written by poet and journalist Scipione Maffei, this instrument is called a “gravicembalo col piano, e forte” (“harpischord with soft and loud”). Another writer, court musician Federigo Meccoli, notes that the “arpicimbalo del piano e’ forte” was created by Cristofori in 1700.

So what was special about Cristofori’s pianoforte? Well, it’s in the name! You may know that “piano” means soft and “forte” means loud. The pianoforte’s main innovation was the ability to play dynamics based on the pianist’s touch: play harder to sound louder; play lighter to sound softer.

This fundamental feature of pianos is often taken for granted today. But in Cristofori’s time, keyboard instruments couldn’t do this well. Clavichords can technically produce touch-sensitive dynamics, but they were compact, quiet, and had limited range. Harpsichords, meanwhile, couldn’t play dynamics based on touch at all because their strings are plucked, not hammered.

Another of Cristofori’s innovations was escapement. This refers to a piano hammer’s ability to fall back immediately after hitting a string, thus allowing the string to resonate longer. He also employed a check mechanism to prevent the hammer from bouncing back and hitting the string, along with dampers to keep strings from resonating when they were not in use.

Cristofori’s piano mechanisms were revolutionary but also complex and expensive. In fact, they weren’t well-received by everyone. Famously, Bach wasn’t a fan, and it took about 100 more years for the pianoforte to be established as a mainstream instrument by musicians. Even Mozart learned his keyboard skills on a harpsichord.

Cristofori’s escapement changed piano playing forever, but it was still rather clunky. French piano maker Sébastien Érard took pianos to the next level by inventing the double escapement. This mechanism enables the player to quickly repeat a note without completely resetting the action, saving time. We can credit Érard with giving us the ability to play fast repeating notes.

This development happened in the 1800s, a full 100 years after Cristofori’s pianoforte burst onto the scene. Rumor has it that Érard showed his double escapement to Beethoven in 1803 and influenced the composer’s ensuing piano works.

Another notable piano maker was Johann Andreas Stein, an Austrian. His piano action, the “Prellmechanik” (often referred to as the Stein action or Viennese action) was very different from Cristofori’s original. The hammer faces the opposite way and the mechanisms are much simpler. The fulcrum is at the end of the key, making it faster and more responsive. These pianos were louder.

While many sources claim Cristofori was responsible for creating the una corda piano, we’re not entirely sure who invented the sustain pedal. It is believed, however, that English piano makers like John Broadwood and Americus Backers were responsible for developing the sustain pedal. Broadwood & Sons is still in business today!

The piano has come a long way. It is, at its core, a fascinating and beautifully complex instrument. The modern piano has around 10,000 moving parts and each key has about 100 parts in its action alone. That’s a lot of parts!

Today, the piano continues to evolve. We have electric pianos that use pick-ups, digital pianos that rely on sampling or modeling, and even hybrid pianos that combine the authentic feel of an acoustic action with 21st-century digital features. Who knows where the piano will take us next?

Related Articles:

As a Pianote Member, you’ll get access to our 10-step Method, song library, and growing community of piano players just like you. Plus: get coached by world-class pianists and learn whenever you want, wherever you want, and whatever you want.

TRY PIANOTE FOR 7 DAYSSources and Further Reading:

Charmaine Li is a Vancouver writer who has played piano for over 20 years. She holds an Associate diploma (ARCT) from the Royal Conservatory of Music and loves writing about the ways in which music—and music learning—affects the human experience. Charmaine manages The Note. Learn more about Charmaine here.

/marketing/pianote/promos/april/banner-bg-m.webp)

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »

/marketing/pianote/promos/april/banner-title.webp)