Have you ever witnessed a musician hear a song and then play it ear, no sheet music required? It’s quite magical, isn’t it?

Guess what? You can learn how to do this!

Playing music by ear isn’t a superpower—it’s a skill anyone can learn and practice. You don’t need perfect pitch; you just need practice.

In this lesson, you’ll learn how to use interval ear training to play your favorite songs by ear.

Don’t forget to download the free lesson resource. Listen to the interval for four measures and then try ti sing or hum it. Once you’ve got that nailed down, try transposing and see how you do in other keys.

Subscribe to The Note for exclusive interviews, fascinating articles, and inspiring lessons delivered straight to your inbox. Unsubscribe at any time.

Intervals are the space between notes. They’re the building blocks to melody because, if you think about it, melodies can be broken down into the movement from note to note.

Therefore, if you understand intervals, you understand how melodies are built. And then you can begin figuring out how to play those melodies by ear.

Some people can identify a pitch (like Middle C) precisely without a reference note. This is called perfect pitch, but it’s quite rare. Only about .01% of the general population (though as high as 4% of practicing musicians) have perfect pitch. Unfortunately, it’s unclear whether we can train people to have perfect pitch (though there have been promising studies) because it appears to be innate. However, anyone can train themselves to have very good relative pitch—the ability to play by ear with references notes.

Many musicians learn how to play by ear by learning how to identify intervals. This is the method we’ll teach you in this post. There are many more ways to improve your ear too, which we’ll share at the end o this post.

A common way to learn and remember intervals is to associate them with popular songs. The following is a list of songs we’ve found that match well with intervals.

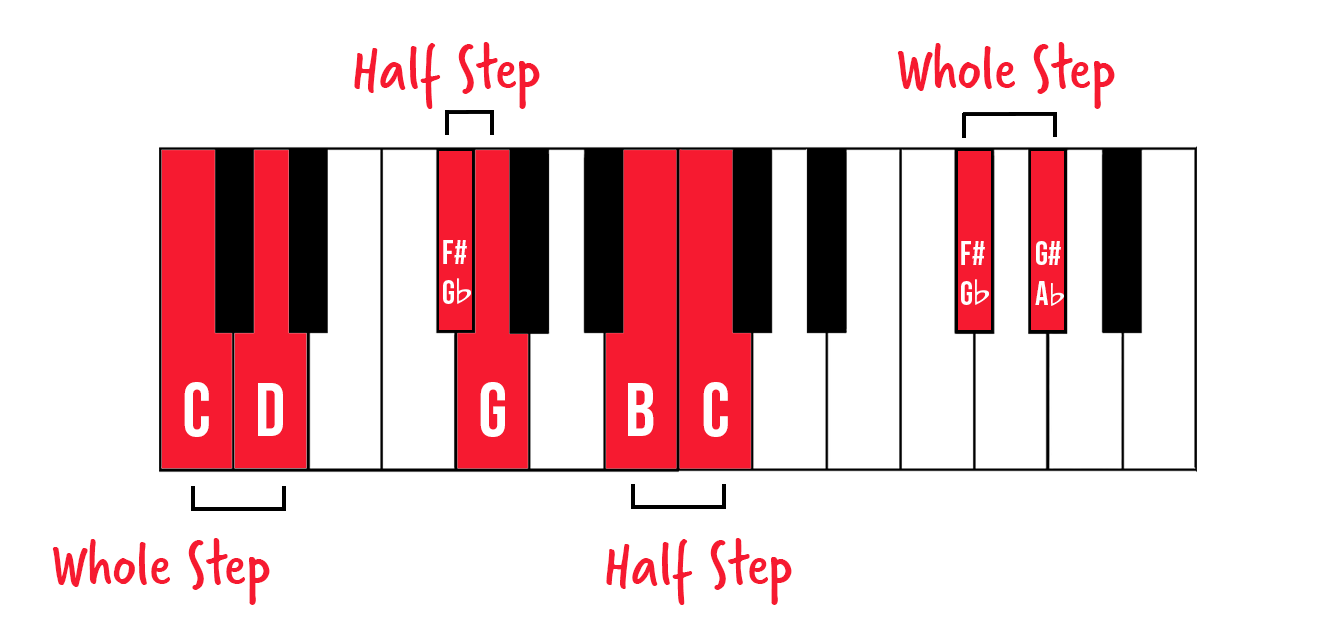

As for the theory behind intervals, you can think of them as degrees of a scale. For example, the first and flat-three of the C Major scale (C and E♭) is a minor third. You can also think of intervals as a number of whole and half-steps.

Scale degrees: 1, ♭2

Half Steps: 1

Whole Steps: N/A

Ascending

Theme from Jaws

John Williams

Scale degrees: 1, 2

Half Steps: 2

Whole Steps: 1

Descending

“Mamma Mia”

ABBA

Scale degrees: 1, ♭3

Half Steps: 3

Whole Steps: 1.5

Ascending

Theme from Spider-Man

(Or, if you’re Canadian, “O Canada”)

Descending

“Hey Jude”

The Beatles

Scale degrees: 1, 3

Half Steps: 4

Whole Steps: 2

Ascending

“When the Saints Go Marching In”

Descending

“Summertime”

George Gershwin

🎹 Tip: “When the Saints Go Marching In” is a handy song because it goes from the major 3rd to the Perfect 4th to the Perfect 5th, so you can use this song for all three of those intervals.

Scale degrees: 1, 4

Half Steps: 5

Whole Steps: 2.5

Ascending

“Summer Nights”

From Grease

Descending

“Under Pressure”

Queen

💡 Fun fact: the perfect unison, perfect 4th, perfect 5th, and perfect octave were named “perfect” in the Medieval era because they were deemed the most pleasing-sounding intervals.

Scale degrees: 1, #4 or ♭5

Half Steps: 6

Whole Steps: 3

Ascending and Descending

“YYZ”

Rush

💡 Fun fact: The tritone is also called the augmented 4th or diminished 5th. It has been nicknamed “the devil’s interval” or diabolus in musica because it sounds so jarring.

Scale degrees: 1, 5

Half Steps: 7

Whole Steps: 3.5

Ascending

Theme from Star Wars

John Williams

Scale degrees: 1, ♭6

Half Steps: 8

Whole Steps: 4

Ascending and Descending

“The Entertainer”

Scott Joplin

Scale degrees: 1, 6

Half Steps: 9

Whole Steps: 4.5

Ascending

“My Way”

Frank Sinatra

Descending

“Man in the Mirror”

Michael Jackson

Scale degrees: 1, ♭7

Half Steps: 10

Whole Steps: 5

Ascending

“Can’t Stop”

Red Hot Chili Peppers

Descending

“The Shadow of Your Smile”

Theme from The Sandpiper

Scale degrees: 1, 7

Half Steps: 11

Whole Steps: 5.5

Ascending

“Take on Me”

A-ha

Descending

“I Love You”

Cole Porter

Scale degrees: 1, 8

Half Steps: 12

Whole Steps: 6

Ascending

“Over the Rainbow”

Theme from The Wizard of Oz

Descending

“Someone to Watch Over Me”

George Gershwin

Once you know intervals by heart, you can start using them to figure out melodies by ear.

For example, listen to the opening phrase of Adele’s “Someone Like You.” Listen to that interval a few times. Perhaps sing it out (it helps!). Then, see if you can match it to any interval reference songs you know.

And hey, it kind of sounds like the opening to “Hey Jude,” doesn’t it?

If you think “Someone Like You” starts with a descending minor third, you’re right! Now play a descending minor third on the piano; contragulations, you have the first two notes of the song.

Now, interval training won’t tell you which note the song starts on, so finding the precise first note might take some trial and error. And depending on what key your song is in and your knowledge of key signatures, some songs may be more difficult to figure out than others. (If you’re new to key signatures, having a handy Circle of Fifths poster nearby may be helpful.)

At first, figuring out songs by ear can feel like a slow process. But with practice, you’ll get faster at doing it. And there may come a point where you’ll start picking up intervals intuitively and instantaneously. This comes with experience.

How do you get better at playing songs by ear? Practice makes perfect, but there are a few extra things you can do:

Singing the melodies you want to play out loud can help you develop a better ear. You don’t need to be a particularly good singer. Just hum the melody. Being able to hum a song accurately means you know the song well and can recreate its intervals. You can then see if you can use that same interval to sing one of your reference songs.

A common exercise in classical piano lessons is the playback. The teacher announces the key, then plays a short melody while the student has their eyes closed or is turned around. The student then tries to play back the melody.

This can be a fun activity to try with a partner. Or, simply listen to melodies you’ve never heard before and try to play them back. You can often find the key by Googling online, if you need a head start.

Transcription is an exercise popular among jazz musicians. Jazz students will listen to the solos of their jazz heroes, play them by ear or write them down (or both), and then practice them in different keys.

Jazz solos (especially piano ones) can be extremely intricate, so this exercise isn’t easy. But some people find the exercise enjoyable, like solving a puzzle. It will also introduce you to jazz vocabulary, vocabulary you can use in your own way in your own solos.

Finally, simply spending time with your instrument and being around music will help. For example, many people can sing their favorite song in the correct key without any reference, simply because they’ve listened to that song a lot.

We hope this lesson helps you in your ear training journey! If you want a more in-depth learning experience and the chance to interact with real piano teachers, try Pianote for seven days for free.

Kevin Castro is a graduate of the prestigious MacEwan University with a degree in Jazz and Contemporary Popular Music, and is the Musical Director and touring pianist for JUNO-winning Canadian pop star, JESSIA. As your instructor at Pianote, Kevin is able to break down seemingly complex and intimidating musical concepts into understandable and approachable skills that you can not only learn, but start applying in your own playing. Learn more about Kevin here.

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »