“Let It Be” by the Beatles is one of the greatest songs ever written, period. Few songs are as legendary or instantly recognizable as “Let It Be.” So, what’s the secret sauce that makes this song great? In this lesson, we’ll dive into the music theory behind “Let It Be.” Don’t worry—it’s not super complicated. In fact, the beauty of “Let It Be” is how Paul McCartney uses very simple music theory in new and creative ways.

Table of Contents:

Subscribe to The Note for exclusive interviews, fascinating articles, and inspiring lessons delivered straight to your inbox. Unsubscribe at any time.

If you’re new to music theory, a chord progression is a continuous pattern of chords that drive the harmony of a song.

The first chord progression used in “Let It Be” is: C-G-Am-F. This is the most popular chord progression in pop music. Seriously, you can find it everywhere—from Adele’s “Someone Like You” to Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood” and Jason Mraz’s “Im Yours.”

This progression is called the I-V-vi-IV progression. It’s called that because it’s built on the first, fifth, sixth, and fourth notes of the C major scale.

In a way, you can argue that “Let It Be” is “basic” because it uses the most common pop progression. But there’s a reason why songs that use the I-V-vi-IV are hits: it just works that well. And re-using chord progressions isn’t necessarily bad or “uncreative”—in fact, we’ll later explain how Paul McCartney puts his own unique spin on the I-V-vi-IV.

> The 1564 Chord Progression, Explained

Intros are what sell a song. It’s the first thing we hear and what we remember a song by. Let’s look at how Paul McCartney composes the “Let It Be” intro.

There’s a clear melody in the song’s opening chords. We hear this melody because Paul uses a technique called inversions. That’s when you re-arrange the notes of a given chord in a different order, changing its sound but keeping its general feeling. For example, Paul moves from a root position C chord (C-E-G) to a first inversion G chord (B-D-G), which keeps that top note (G) constant. The top note is what we hear as the melody.

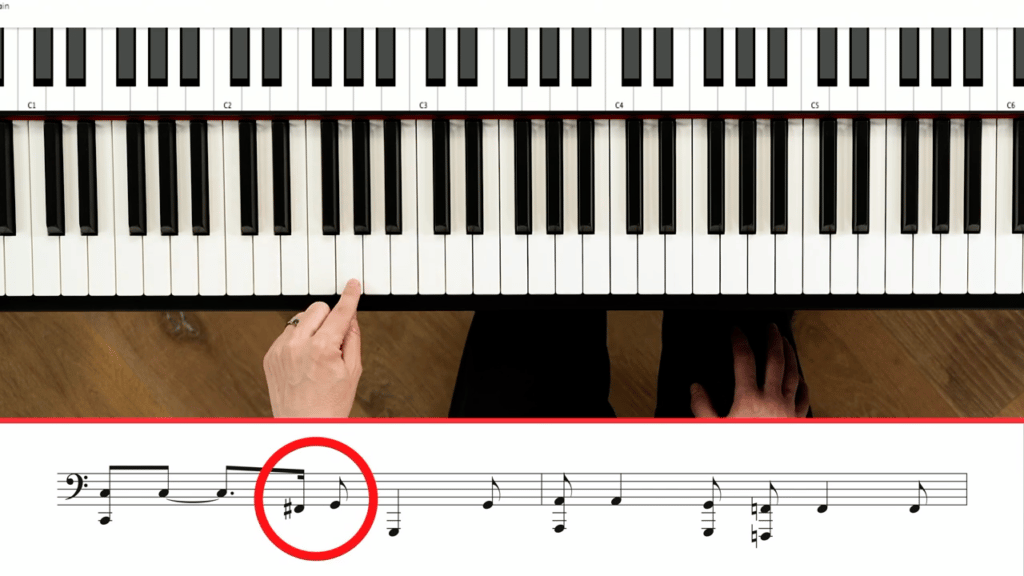

The second time this intro is played, Paul uses fuller, four-note chords. He also skips the Am chord and instead plays the small, iconic riff that ends the intro:

The left hand is also worth mentioning. For the most part, it plays a simple bass line based on the root notes of our chord progression. But, Paul does insert a funky chromatic passing tone here that belongs outside of the key.

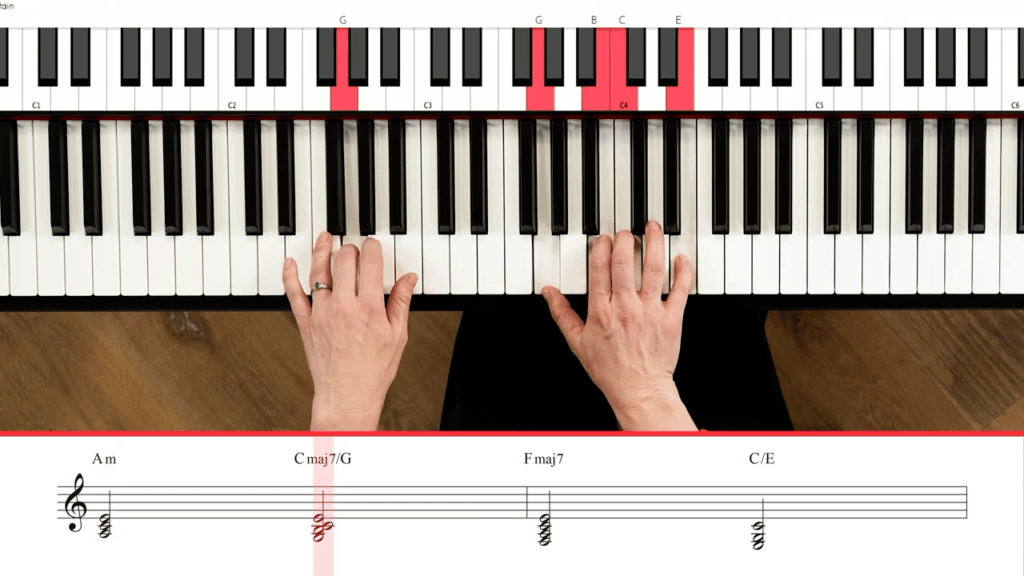

What’s cool about the chorus is that Paul uses the same chords; he just mixes up their order. So instead of going C-G-Am-F, we hear:

(The Cmaj7/G functions similarly to the G chord.)

But let’s look at the melody. What I love about the melody is that it’s based on the pentatonic scale. Pentatonic scales are neat because these five-note scales can be found across many cultures, making them a universal musical concept that humans just love.

The pentatonic scale also doesn’t have much tension. This is unlike major and minor scales, which want to resolve to something. Instead, pentatonic scales just kind of float around and sound good. I find it so incredible that this is the scale used in a song called “Let It Be”!

We end the chorus with a plagal cadence. That’s a IV-I chord movement. Plagal cadences are common in hymns and spiritual music. Moving back to the I creates a feeling of resolution and satisfaction.

We end with that iconic walkdown. The chords may look complicated, but if you look at the left hand bass notes, it’s just a scale walking down. Remember that Paul McCartney is a bass player! He likely found a neat bass line and then found chords to fit into that scale.

This scale that Paul uses is called the C Mixolydian. You can think of C Mixolydian as F major starting and ending on C. That’s why there’s a B-flat (flat 7) here. The Beatles also use this trick in “Hey Jude,” and later on, more pop artists would jump on this trend, including bands like Guns ‘N Roses, Boston, and Green Day.

The walkdown is also made possible with slash chords. This means we play the chord before the slash with our right hand and the note after the slash with our left hand. Slash chords create a more unique walkdown effect than if we’d simply gone down using our root notes.

So, what can we learn from “Let It Be”? Things that can help all of us become better musicians! I can think of three main points:

We hope this lesson lets you appreciate one of history’s favorite songs even more. And if you want to learn how to play “Let It Be,” we have a free, step-by-step tutorial right here!

As a Pianote+ Member, you’ll get access to our 10-step Method, song library, and growing community of piano players just like you. Plus: get coached by world-class pianists who have played with rock stars.

Lisa Witt has been teaching piano for more than 20 years and in that time has helped hundreds of students learn to play the songs they love. Lisa received classical piano training through the Royal Conservatory of Music, but she has since embraced popular music and playing by ear in order to accompany herself and others. Learn more about Lisa.

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »