Music theory rules can be confusing. Sometimes, they don’t even make sense! (At least to me.) In this lesson, I sit down with Sam to discuss some of music theory’s weirder rules. You’ll see that we disagree on whether these rules should be followed, and we each have some very strong opinions!

Here’s what we’ll talk about:

Now, as much as I disagree with him from time and time, Sam does an excellent job explaining all these rules. So, if you’ve ever been confused about the difference between ties and slurs and how to tell them apart keep reading!

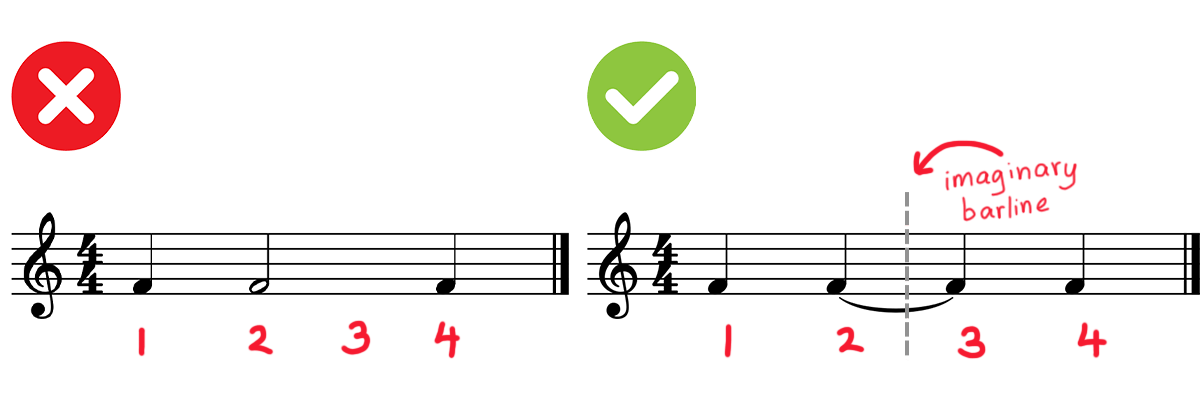

The invisible bar line or the imaginary bar line is a rule for writing sheet music. Imagine that an invisible bar line cuts through each measure of music, splitting it into two equal halves.

The rule is you can’t cross the invisible bar line. This means you typically cannot combine beats 1 and 2.

In the first, incorrect measure, beats 2 and 3 are combined into one half note. In the second, correct measure, beats 2 and 3 are written separately. But both versions sound the same.

Now, the invisible bar line rule sounds pretty unnecessary to me! But according to Sam, organizing measures into two equal parts makes it easier for musicians to read very complex sheet music. For example, this rule can help musicians read syncopations.

🎹 The invisible bar line rule debate goes on! Interestingly, not everyone agrees that the imaginary bar line makes things easier to read (take that, music theory rules!). In fact, someone did an informal poll and many musicians seem to prefer the “incorrect” way of writing things…If you want to learn more about this rule, check out Berklee’s music theory lesson for a more academic explanation.

Ties and slurs look way too alike. They both involve sweeping, curved lines across sheet music. So what’s the difference?

Well, when two identical notes are connected, it’s a tie. A tie is when the note values are added together. So, two quarter notes tied together is basically a half note.

A slur is when several different notes are connected together with a curved line. (Sometimes, this is called a phrase.) This means that the notes should be played legato or connected, and it’s kind of like singing a series of notes in one breath.

See, my question is this: why don’t we just invent different symbols for each thing? Like have a squiggly line mean a slur?? Well, Sam’s answer is that this is just convention handed down to us from the people who made the rules.

This explanation doesn’t satisfy me, but it’s too late in history to change things!

You may have seen a staccato and a tenuto, but have you heard of staccatissimos and mezzo staccatos?!

These little articulation markings are super specific types of staccato!

Personally, I think we should just rely on the emotion inherent in the music we’re playing. And Sam says I have a point! But knowing the tools to express musical feeling on paper can also be useful.

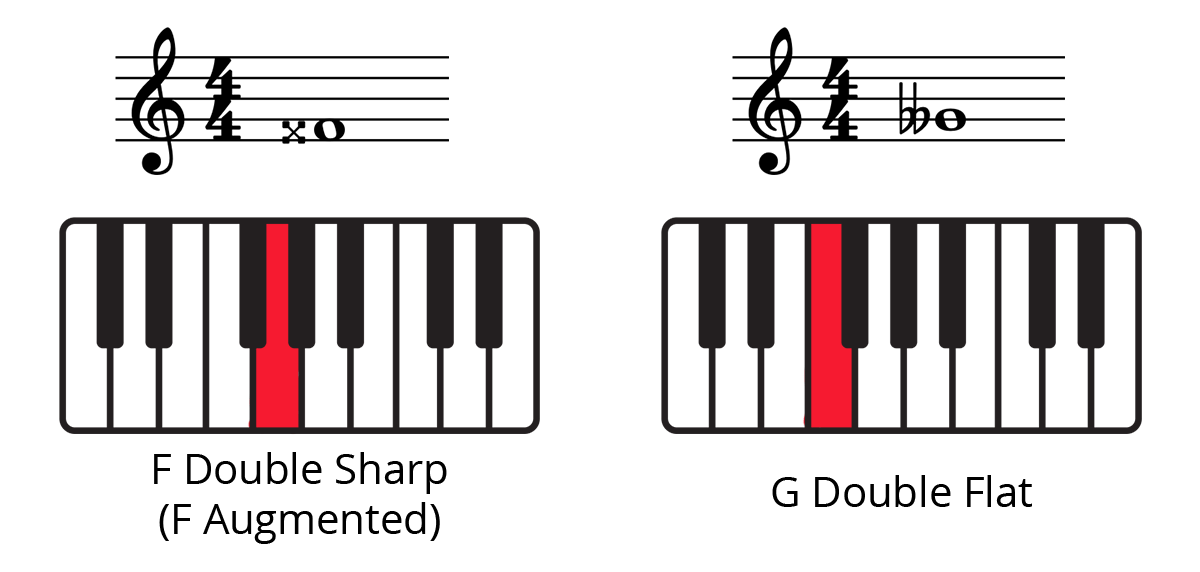

Yup, you can double-sharp and double-flat a note.

Double-sharps look like an “x” and double-flats are just two flats. A double-sharp raises a note’s pitch up by two semitones, and a double-flat lowers a note’s pitch down by two semitones.

In this example, F double-sharp is the same note as G. And G double-flat is the same place on the keyboard as F.

So, here’s the obvious question: why don’t we just write G and F for these two cases?!

Here’s how Sam explains it: double sharps and double flats prevent the key signature from interfering with a natural sign if there was ever to be one in a challenging key. So, double sharps and flats allow us access to the natural notes we want to use without having to change the key signature.

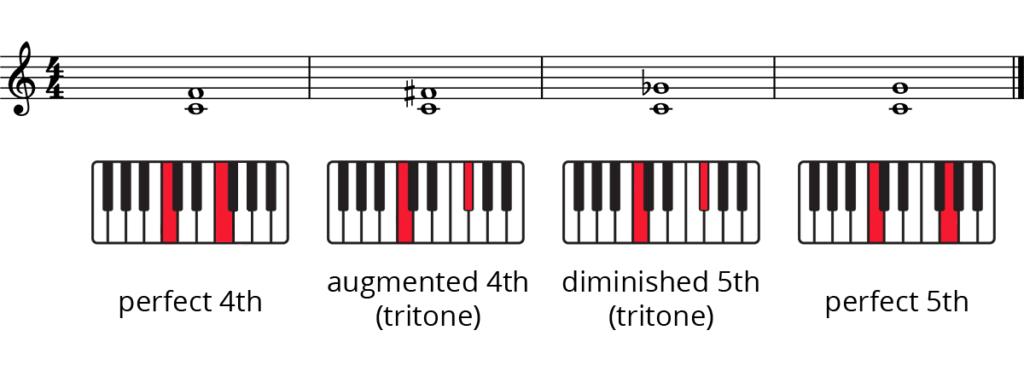

The tritone is a funky, crunchy sounding interval that exists between a perfect fourth and a perfect fifth.

Another way to describe this is an interval three whole steps apart.

When it comes to intervals, most intervals have a major version and a minor version; for example, we have major thirds and minor thirds. But perfect fourths and fifths don’t have two versions.

However, we can narrow a perfect fifth by one half-step or widen a perfect fourth by one half-step. This gives us a diminished fifth or an augmented fourth, respectively, also called a tritone.

📜🎹 HISTORY BITE! The tritone was avoided for much of the Middle Ages because it was difficult to sing and sounded bad. It was even nicknamed “the devil’s interval” (diabolus in musica). Today, the tri-tone can be found providing a dramatic flair to everything from classical to rock to musicals.So, now we want to hear from YOU. Do you think these music theory rules are necessary? Leave a comment on our YouTube video!

Lisa Witt has been teaching piano for more than 20 years and in that time has helped hundreds of students learn to play the songs they love. Lisa received classical piano training through the Royal Conservatory of Music, but she has since embraced popular music and playing by ear in order to accompany herself and others. Learn more about Lisa.

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »