If piano music theory makes you frustrated, you’re not alone!

Music theory can be a very dense, very complex subject. After all, people do entire post-graduate degrees in this stuff.

But piano music theory doesn’t have to be complicated to be useful.

In this post, we’ll show you piano music theory you can use starting today. Theory that actually helps you play your favorite music on the piano.

And guess what? You don’t even need to know how to read music. In this lesson, we’ll cover:

Ready? Let’s get started!

Inspiring tutorials. Fascinating articles. Exclusive interviews. We create piano content anyone, anywhere can enjoy for free. Don’t miss out, sign up for more free lessons.

Why is it important to know your scales? Because understanding scales helps you understand keys. And most songs use chords that are built on the notes of a particular scale.

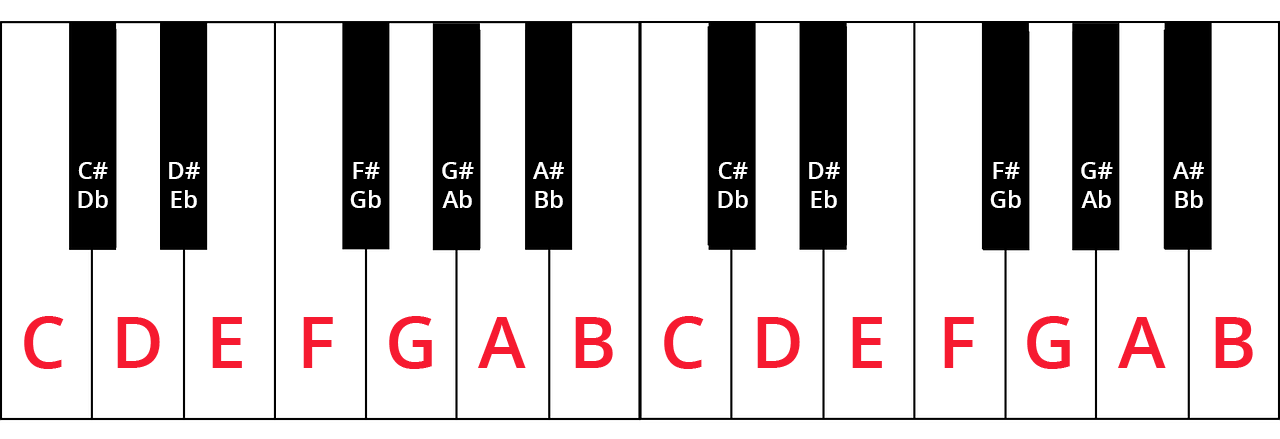

While you don’t need to know how to read music to benefit from this post, it will help to know the names of the notes on your keyboard. Feel free to refer to this diagram (note that black keys have two possible names):

Major keys (such as G major, E flat major, or F sharp major) sound “happy.” They’re likely the first type of key or scale you’ll learn.

Each key has its own character. For example, C major has no sharps or flats, but B flat major has two flats.

To figure out how many sharps or flats a major key has, there are formulas you can learn such as the Circle of Fifths. However, if you know the major scale formula that underlies every major scale, you only have to memorize ONE thing!

Here’s the formula:

W – W – H – W – W – W – H

The Ws mean whole-step and the Hs mean half-step.

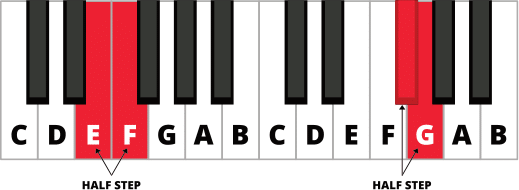

A half step — also called a semitone — is the distance between one key on the piano to the one immediately next to it. For example, C to C sharp (the black key just right of C) is a half step. E to F (two white keys right next to each other) are also half steps from each other.

A whole step — also called a whole tone — is made up of two half-steps. For example, C and D is a whole step apart because a black key (C sharp or D flat) is the half step between them.

Here’s how you build the G major scale using this formula:

Notice that going from E to F sharp — a white key to a black key — is a whole step.

If we put everything together, the G major scale looks like this:

G – A – B – C – D – E – F# – G

Minor keys sound a little moody.

Similar to major scales, you can build any natural minor scale in any key using a formula of whole and half tones:

W – H – W – W – H – W – W

…But you can get away with not memorizing this formula if you understand relative minor and major keys. Every major key has a relative minor key and vice versa. Relative keys use the same notes and the same number of sharps and flats; they just have different starting points.

If you want to find the relative minor key of a major key, simply count down three half-steps. If you want to find the relative major key of a minor key, count up three half-steps.

Here’s an example:

So, E minor is just G major except you start and end on E.

E – F# – G – A – B – C – D – E

You may have heard that there are different types of minor scales:

To play songs with chord progressions, understanding natural minor scales should be enough. But knowing other types of minor scales may help you craft riffs and fills.

> For a deeper dive into scales, check out Piano Scales: Types of Scales and How to Apply Them

Love more guides like this? Subscribe to The Note for more quick tips, cheat sheets, explainers, and other stuff piano players love. Delivered to your inbox for free.

A triad is a three-note chord and is one of the first chords you’ll learn on the piano. They’re also incredibly useful!

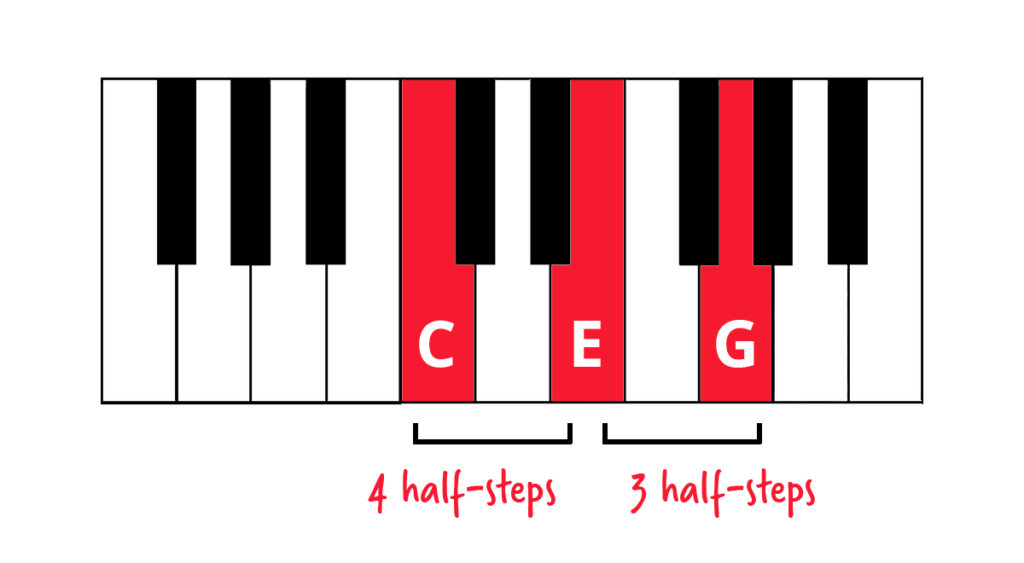

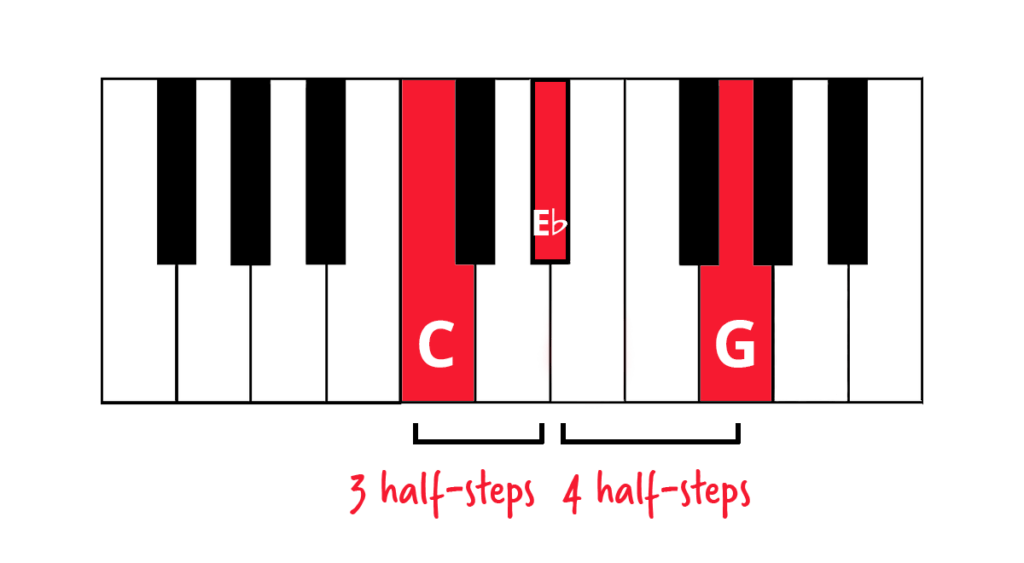

Using whole steps and half-steps, you can also build major triads and minor triads in any key using these formulas:

Play these triads with your 1, 3, and 5 finger. We like to call this shape “the Claw.” If it feels funky at first, don’t worry. That’s normal. The more you practice, the more natural this chord shape will feel.

Now try moving the same 1-3-5 claw shape up the G major scale. In other words, build a triad on top of every note of the G major scale. You’ll end up building the following chords. If you’re wondering why there’s an F sharp — remember, we’re in G major and G major has one sharp, F!

| Scale Degree | Notes in Triad | Name of Chord | Chord Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G-B-D | G major triad | G |

| 2 | A-C-E | A minor triad | Am |

| 3 | B-D-F# | B minor triad | Bm |

| 4 | C-E-G | C major triad | C |

| 5 | D-F#-A | D major triad | D |

| 6 | E-G-B | E minor triad | Em |

| 7 | F#-A-C | F# diminished triad | F#dim |

The small “m” means these chords are minor chords and will sound moodier. Don’t worry too much about the F#dim chord for now — it’s just a minor chord where the distance between F# and C is less than a perfect fifth; therefore, “diminished.”

Once you can do this, it means you’ve found every major and minor chord in the G major scale. This unlocks many, many songs in G major! So, congrats!

The fancy word for these types of chords is diatonic chords. We also have a more detailed lesson on building diatonic chords here.

The 1-5-6-4 chord progression is one of the most common chord progressions in modern Western music. Once you know it, you basically have the ingredients to play every pop song ever written. No, I’m not kidding — in fact, this exact same progression is used in “Someone You Loved” by Lewis Capaldi (check out a tutorial on how to play that song here).

The 1-5-6-4 progression is simply building chords (like we did in the previous section) on the first, fifth, sixth, and fourth note of the scale. In G major, this will be G major > D major > E minor > C major.

G – D – Em – C

People sometimes write this in Roman numerals, with the lowercase letters representing a minor chord:

I – V – vi – IV

This is called the Nashville Numbering System and it’s useful to learn because it lets you transpose a song into any key. You can learn more about this system here.

Rhythm sometimes gets shoved to the side among us pianists, but it’s an important part of music-making and you should understand the basics.

Let’s take “Someone You Loved.” Hum and tap to the beat of “Someone You Loved” and you’ll find that it fits into this counting scheme:

1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4…

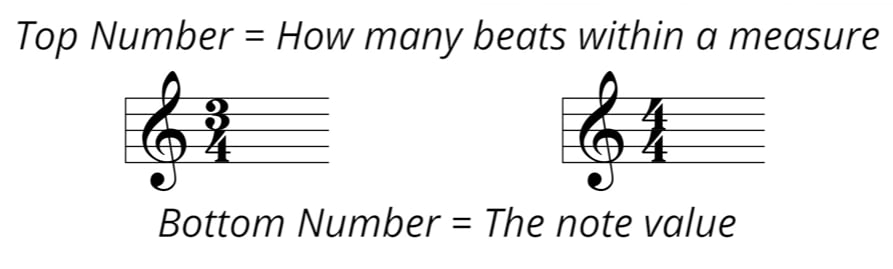

This is called 4/4 or “common” time. In sheet music, it’s written out like this: 4/4. The top four means that in each measure, there are four beats. The bottom four means that a quarter note takes one beat.

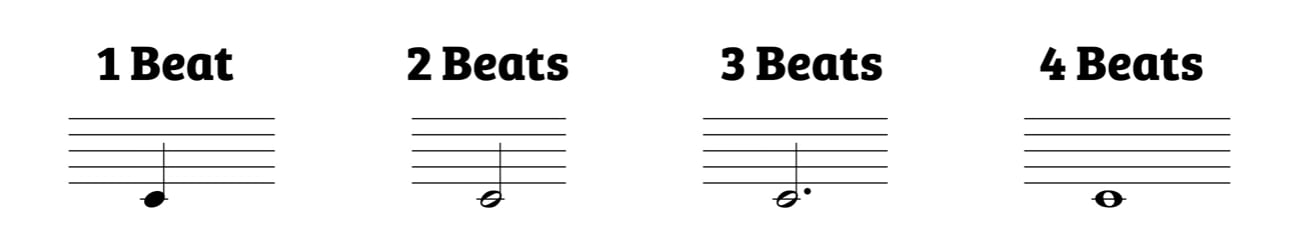

This is how many beats each type of note is “worth” in 4/4 time:

And this is what those notes look like:

So, if we play “Someone You Loved” in quarter notes in 4/4 time, this is the rhythm we play:

Let’s take a look at this in action!

Here’s me chording a song in quarter notes.

And here’s chording in half notes!

Finally, here’s me chording with whole notes 🙂

Music is made up of different ingredients 🧑🍳 such as:

So, if you know these ingredients well, you can make a song!

Now, songs are often in different keys, but if you understand the scale formula, you can make a scale in any key.

Then, once you have that scale, use it to make chords.

Then, use those chords to make a chord progression.

…And then, mix up the rhythm to create your own unique song!

We hope this piano music theory lesson is helpful. If you want a more in-depth look at how music theory works, check out Music Theory for the Dropouts or our How to Read Notes tutorial. Happy practicing!

Your musical journey starts today: try Pianote and get access to drum, vocal, and guitar lessons too!

Lisa Witt has been teaching piano for more than 20 years and in that time has helped hundreds of students learn to play the songs they love. Lisa received classical piano training through the Royal Conservatory of Music, but she has since embraced popular music and playing by ear in order to accompany herself and others. Learn more about Lisa.

By signing up you’ll also receive our ongoing free lessons and special offers. Don’t worry, we value your privacy and you can unsubscribe at any time.

We use cookies for traffic data and advertising. Cookie Policy »

/marketing/pianote/lead-gen/digital-chords-and-scales/blog-exit-m.png)

Grab a FREE E-Book with every Chord and Scale you’ll need to play your favorite songs.

Enter your email and we’ll send your book instantly.

Don’t worry, we value your privacy

and you can unsubscribe at any time.